[Summary of the presidential address delivered at the Vivekananda birthday celebrations at the Ramakrishna Mission, New Delhi, on the 25th February, 1940.–Ed]

I readily accepted the invitation to be present here this afternoon and to take part in the proceedings, for the simple reason that for the last 36 or 37 years I have come under no greater influence than the influence of the life and teachings of Swami Vivekananda. In my own province, on several occasions, I have spoken of that life and have testified to the great influence that that life has had on the generation which immediately succeeded the premature departure of the Swamiji from this world. In England on more than one occasion I had the opportunity of either presiding or taking part in similar celebrations, and to-day I am not coming for the first time to this Ashrama, but I am repeating for the third time the happy experience that I have had before of partaking in this function, for in the days when I used to come to this city as a much bolder non-official representative — an advocate of public opinion — I had the privilege of taking part in such celebrations. On this occasion, I can repeat what I said to a Calcutta audience on a similar occasion-—that we in Madras feel proud that it was left to us to discover the greatness of Swami Vivekananda when as a nameless individual wearing the orange robes of a sannyasin he came to Madras not knowing what his programme was, with the burning desire that he should somehow or other attend the meeting of the Parliament of Religions at Chicago.

Soon after I began to study in the college, there were friends and elders of mine who used to tell us stories of the days in 1893 when Narendra Dutta— (Swami Vivekananda) as he then was— often sat on the pials of the houses of Triplicane and began to discuss with learned pandits in Sanskrit—and some of them in Madras were very learned indeed – the great truths of our religious teaching. The exposition, the dialectic skill he showed, and the masterly way in which he analysed what even to those well-educated and learned Pandits were unfathomable depths of Sanskrit literature and law, greatly attracted attention from all and sundry and it was an evening function well worthy of the sight of the gods themselves to see great professors of colleges and learned folk sitting round him in the pial and trying dialectic debates with him on the meaning which should be given to this or that particular sloka of Patanjali or of the Gita. His worth was tested and he became famous and had all the help that was necessary to send him to Chicago.

The tremendous sensation he created at the World’s. Parliament of Religions and the wild wave of enthusiasm that ran through tens of thousands of people when this orange-robed young figure of thirty got up and addressed a distinguished gathering, in those immortal words, “Sisters and brothers of America”, giving that touch of universal brotherhood, the keynote of the religion which he expounded, are matters which we love to read over and over again. Forty years after that first Parliament of Religions, a similar one was held in connection with the Great Fair in Chicago in 1933, and by a curious combination of circumstances, I happened to be at that Fair and, of course, took the opportunity of attending the Second Parliament of Religions. The magic personality of Swami Vivekananda was not there-—he who used to be reserved as the last speaker, the one magnet who would attract all and keep the entire audience bound to their seats.

I missed that charm, that magnetic and great source of influence and of light which welded together that happy mass of religious heads, scientists and students who had gathered in the First Parliament, but I met there old men and old women, citizens of America who still remembered the First Parliament of Religions and whose minds and hearts were impressed indelibly for all time to come with the immortal features of Swami Vivekananda -and the immortal words that he preached to the great audience.

So much has been said of Swamiji’s life and teachings. What was it that he intended to do? His early life, his coming into contact with Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, his first tendencies, irreverence, unbelief in all superstitions—they have all been referred to ; but it was later that the golden touch of his Master transmuted the collegian into a sage and a saint ; of that I would like to speak.

“Whenever there is a case of vice triumphing then I am born again and again to rejuvenate the world”, said the Great Lord. I do not want to enter into any controversy as to who was and who was not an Avatar. But I venture to repeat what Swami Vivekananda himself so often said that the race of Avatars is not yet exhausted and will never be exhausted. ‘Time after time these great souls are born in all climes and in all periods whenever God feels the need for fulfilling aims and bringing back the world into His ways again. So was Narendra Dutta and so his mission first and foremost was to his own countrymen to tell them to have confidence in themselves, to ask them to reread their Bibles, to make them realise the eternal verities of their religion, not to be carried away by cultures from the outside world—all that was half understood—but to ‘drink deep of the spring which their ancestors left for them. He carried that mission through the length and breadth of India, in his own speeches from Colombo to Almora in the triumphal tour that he made after his return from that Parliament of Chicago. He was a humble sadhu unknown, with no pretensions to high aristocracy, holding no position in life, wearing the simple orange robes of one who has to a large extent given up all that is held materially valuable in this world, and his procession was one which Kings and Emperors and Fuehrers and Duces may envy for all time.

He was in touch with the masses. His soul responded to their crying need, and as he went from Colombo to Almora halting at several places which were fortunate enough to receive his visit, he expounded the truth that lay in him. First and foremost he told them that no religion was superior to another and that all religions have the same cardinal principle of truth. That is indeed what the Lord has said long long before: as several rivers flow and ultimately merge themselves in the great ocean so all religions lead to the same eternal and inevitable goal. In one of his speeches he says Hinduism, Christianity, Islam—they are all religions. I respect them all. I believe in them all. But I do not believe in conversion from one religion to another. You put the seed in the ground. There is the earth; there is water; and what do all these give you? Not the earth, not the water, not even the seed, but a plant which resembles none of these things, which is a product of something quite different from the elements in which it was placed. So it is the soul that derives the divine inspiration.”

I remember the glorious passages in one of his speeches where he speaks of toleration. This was a great land, the eternal punyabhumi which, age after age, century after century, in its own borders through its great religion, Hinduism, has preached and practised the doctrine of toleration. Here came the refugees from all the religions in the world, persecuted by fanatics who understood less of their religion than they thought they did, refugees from the West Christian Church to the Syrian Church of the East, and then came refugees from the Zorastrian religion and from all and sundry, and there was no question of – this great land of God refusing them shelter; nay, more than that, of giving encouragement to all these people of all religions, men persecuted for their religious faith, driven from their hearths and homes, well-nigh treated worse than brutes. We may take some satisfaction in the fact that these sages like Swami Vivekananda have still retained that dominant principle of Hinduism which realised that all men have the same divine essence in them, that all men are the parts of the same divinity and that therefore there is no religion‘ higher than that which preaches the brotherhood of man.

Reference was made to the remarkable scene of Kurukshetra when Arjuna threw up his bow and arrow and told Sri Krishna that he ‘Was unable to fight. If there was one book more than another which Swami Vivekananda constantly referred to, which I believe was a sort of inspiration perpetually to him, it was the Bhagavad Gita and in more than one speech you will find that he refers to this incident or that and draws the lesson which he feels proper. “Resist not evil” is a canon which finds place in almost all religions. Its meaning is very often misunderstood. “Resist not evil”—it is true. Swami Vivekananda explains what that means. It is not that lack of physical courage which makes man a coward before superior force. Swami Vivekananda was a fighter himself. He was one who knew not any kind of physical cowardice or moral cowardice. He had a perfectly developed physique. I heard stories when I was young of how he got into a first-class carriage on the M. and S. M. Railway wearing this orange garb and somebody got in and asked Swamiji to get down and tried to abuse him. The Swamiji got up his powerful arm, forgetting for a moment the orange robes, took him by the grip of his neck and threw him on the platform. Not because he was a Swamiji, not because he wore the orange robe which he never thought, should cover an overwhelming physical force, of which there was much in him. That is the lesson which Swami Vivekananda tried to force. He said it was no good of a religion to a people who were starving for bread. They should have courage, physical courage—first of all a sound body and then a sound mind.

Well, as I said, we are grateful to Bengal for having given us Swami Vivekananda. He is a citizen of the world. His contribution will stay on for ever. His immortal soul pervades the whole universe. But Bengal still can claim rightly the proud privilege of having contributed so great a soul.

From our Archives: Published in Prabuddha Bharata, April 1940.

[hr]

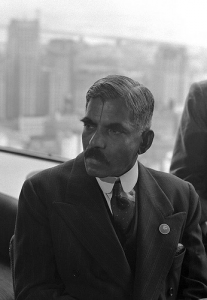

Sir Arcot Ramaswami Mudaliar

Padma Vibhushan Diwan Bahadur Sir Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar, KCSI(b. October 14, 1887 – d. July 17, 1976) was an Indian lawyer, politician and statesman who served as a senior leader of the Justice Party and in various administrative and bureaucratic posts in pre-independence and independent India.

Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar was born on October 14, 1887 in the town of Kurnool and had his schooling in Kurnool. He graduated from the Madras Christian College and studied law at the Madras Law College. On completion of his studies, practised as a lawyer before joining the Justice Party and entering politics. Mudaliar was nominated to the Madras Legislative Council in 1920 and served from 1920 to 1926 and as a member of the Madras Legislative Assembly from 1931 to 1934. He served as a member of the Imperial Legislative Council from 1939 to 1941 and as a part of Winston Churchill’s war cabinet from 1942 to 1945. He was India’s delegate to the San Francisco Conference and served as the first President of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. He also served as the last Diwan of Mysore kingdom and occupied the seat from 1946 to 1949.

The present article is the summary of the presidential address delivered at the Vivekananda birthday celebrations at the Ramakrishna Mission, New Delhi, on the 25th February, 1940. His personal reminiscences and his analysis of Swamiji’s message make this article both interesting and valuable.

(The last segment of Swamiji physically intimidating somebody is a part of oral lore, which we do not find in his published biographies – Webmaster)