Sri Ramakrishna

The Guru-power was manifested to its highest degree in Sri Ramakrishna. The Yoga-Sutras say: Sah ptirvesam api guruh, kalena anavacchedat, ‘God is the Guru of all ancient gurus, because He is not subject to time.’ To Sri Ramakrishna the word ‘guru’ applied in its fullest sense. Although he never had the consciousness of being a guru, whatever he said and did was what a guru does to disciples – namely, to awaken them spiritually and also to free them — yasmat bandha-vimoksanam.

Sri Ramakrishna’s life can be divided into two parts — the first, as a sadhaka, an experimenter in the field of religion, and second, as a guru, a teacher of humanity. As a sadhaka he was concerned with his search for God and had no time or mood to deal with people, to talk to them, and mix with them. For about twelve years he was so absorbed in God and in experimenting with various religions that he kept himself away from the company of others. He practised the various spiritual paths in the Hindu religion, which can be broadly classified into two — jnana marga and bhakti marga. He went through all the paths within the bhakti marga; this included, later on, Christianity and Islam as well. Then he practised the jnana marga, the path of advaita. God is worshipped as saguna, as a person with qualities, in the bhakti marga, and as nirguna, impersonal, without attributes, in the jnana marga. These two paths are not contradictory, he was to say later on; the same God is both saguna and nirguna. When Sri Ramakrishna completed the jnana marga sadhana, he attained nirvikalpa samadhi, taking his mind beyond the world of relativity. He remained in that state for six months, forgetful of his body and oblivious of the passing of days and nights. In that absorbed state, a wandering sadhu who was staying at Dakshineswar temple at that time used to feed Sri Ramakrishna. Sometimes, the sadhu had to feed him forcibly to keep his body alive, because the sadhu realized that Sri Ramakrishna’s body was so precious that it should somehow be preserved for the good of humanity.

After remaining six months in that transcendental state, Sri Ramakrishna heard the Divine Mother speaking to him: tui bhavamukhe thak, ‘You remain in the state of bhavamukha, the threshold of relative consciousness.’ After this, he became completely transformed, and it is this transformed, divinely human Ramakrishna that appeals to you, to me, and to millions of people all over the world, as the guru of all. This message from the Divine Mother brought about a revolutionary change in Sri Ramakrishna’s personality. Till then he did not relish human company, but now he sought it. He wanted to talk to people. This intensely human element made his charming personality all the more charming. He felt a keen desire to scatter among the people the great truths he had gathered during the twelve years of his sadhana.

But Sri Ramakrishna could never bear worldly talk. The people around him, mostly priests and other temple staff, were all worldly. He would climb up to the roof of the building nearby and, looking towards Calcutta, would cry out: ‘Where are you all ‘? Please come! I cannot live without you.’ The Divine Mother had assured him that there were spiritual seekers waiting. His various sadhanas were over by 1872. This yearning to commune with humanity arose in him soon after.

Now a wonderful thing happened. People started coming from Calcutta to Dakshineswar, hearing that a great spiritual personality was living there. All types of people — pious, literate, illiterate, atheists, men, and women — started coming. Among them were a few spiritual leaders like Keshab Chandra Sen and other prominent members of the Brahmo Samaj. There came to him the orthodox and the unorthodox, the traditional and the modern, scholars and orators, and also simple housewives. They were immensely impressed by seeing him and talking and listening to him. Keshab Sen and some others wrote in their papers about Sri Ramakrishna. That made the trek of the people and seekers grow into a procession from Calcutta to Dakshineswar, a procession which is continuing even today and includes all of us!

Among those who went to him at that time were a few young men like Naren and others, mostly students, in the age group of 14-20 years, and older householder devotees. To everyone he gave according to his or her capacity to assimilate spiritual ideas. The older people could not grasp new ideas about spirituality. So to them he gave the traditional ideas, but in a purer form. Usually they could come only on holidays. He talked to them, and one of them, named Mahendra Nath Gupta or M., recorded his talks, which today we get as the great book, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. The younger ones came to him on holidays and also on weekdays. Sometimes they stayed with him overnight. To them he gave something new or an understanding of the old in a new, dynamic form meant for this yuga. It is that type of teaching which we find Swami Vivekananda proclaiming later to humanity in the East and the West. The Gospel contains these teachings only in a seed-form, in hints and suggestions, especially when Sri Ramakrishna addressed Naren, later Vivekananda.

Before Sri Ramakrishna’s passing in 1886, he gave these teachings to Naren and other young disciples whom he formed into a monastic sangha. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna is an extraordinary book of spirituality. In it you get pure Sanatana Dharma in its universal form. You do not find in it any dogmas or doctrines, but something that can awaken humanity spiritually. In fact, Sri Ramakrishna would pray to the Divine Mother thus: ‘Mother, let not my mouth expound any doctrine.’

There are several chapters in the Gospel titled ‘Advice to Householders.’ We Indians, especially our householders, during the past few centuries, had lost faith in ourselves. Everyone was possessed by the meek attitude: ‘We are, after all, samsarins, worldly people; what can we do ‘?’ Sri Ramakrishna came to remove this negative attitude. You are in samsara, but you should not allow samsarikata, worldliness, to enter into you. Someone asked him, ‘Sir, we are householders. Can we realize God? Promptly came the reply, ‘Certainly, you can realize Him. God can be realized by all. He is our own Inner Self.’ Through Sri Ramakrishna, the Holy Mother and Swami Vivekananda, householders of today and the future will develop a new sense of joy, a sense of self-reliance, and a spirit of social and national responsibility.

Sri Ramakrishna and the Holy Mother lived as householders of a unique type. Our householders in India have to realize that they can grow spiritually, develop a sense of social responsibility, and grow in spiritual awareness and human concern, beyond the little genetic group called grhastha or householder. That is the growth from the unripe-I to the ripe-I. They must grow into citizens of the nation, citizens of the world. That is the sign of spiritual growth, atma-vikasa. They must cultivate vidya maya, and rise above avidya maya. ‘I and mine’ is maya, ‘thou and thine’ is daya, says Sri Ramakrishna.

One characteristic of Sri Ramakrishna’s personality is the sense of joy in him. Joy is a characteristic of true religion. Sri Ramakrishna showed that the joy of religion is greater and more intense than the joys of worldly life. He used to sing: Ei samsar hocce majar kuthi, ‘This world is a mansion of mirth.’ Since God is present everywhere, the world is indeed a mansion of mirth.

Sri Ramakrishna’s teachings contain illustrative parables and stories which can teach us many lessons. Though he had only an elementary education, he could discuss philosophical and spiritual ideas with scholars and astound them. One day he went to meet one of the greatest pundits of Calcutta at that time, Sri lswar Chandra Vidyasagar. This meeting, and the 4-hour dialogue, is recorded in the Gospel. It is simply marvellous. It describes how a great scholar got some lessons from this semi-literate person. Sri Ramakrishna was very humorous. Generally, religious people are not humorous and joyous, but Sri Krishna and Sri Ramakrishna were exceptions. So when Ramakrishna met Vidyasagar, the first thing he said was, ‘I am glad I have come to the “ocean” today. Till now, I have been only to tanks and lakes.’ Vidyasagar was also humorous. He said: ‘Then you are free to take some salt water from the ocean.’ Sri Ramakrishna countered, ‘No, no, why salt water‘? You are not avidyasagar, ocean of ignorance, but vidyasagar, ocean of knowledge!’

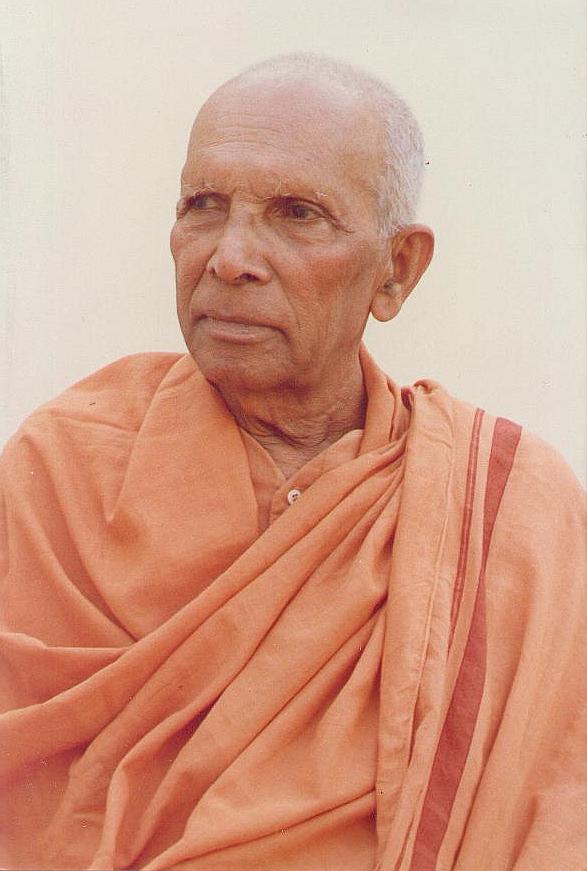

Swami Ranganathananda

In the course of the dialogue, Sri Ramakrishna remarked that all the holy books in the world are ucchista, meaning, left-over after-meals, since they have been uttered by the human mouth. Only Brahman, the ultimate Reality, is not ucchista, because no one has been able to expound Brahman by mouth. Vidyasagar was deeply impressed by this statement and said, ‘Please repeat it once again, sir; it is beautiful.’ Vedanta speaks of Brahman as being beyond speech and thought. You cannot express Its nature through mind or mouth.

Sri Ramakrishna conveyed to his listeners on another occasion a beautiful teaching which will help all of us in our day-to-day life, helping us to grow spiritually. I referred to it cursorily earlier — the little-I in all of us and how to handle it. Every human child develops the sense of ‘I’ at the age of about 2½ years. Nothing else in this world —the sun, stars, planets, or animals — has this sense of ‘I’. Only humans have it. And that is a source of tremendous power to all human beings. It is through this that the human being dominates the whole of nature. How to handle this ‘I’ which appears in all of us as a central truth‘? It is a profound subject of interest in the whole world. The baby gets the feeling of ‘I’, and when it starts saying ‘I want this, I will do this,’ it has started on the long, truly human journey to atma-jnana. We want to know what is the nature of that unique datum and that unique journey. It is not anything magical or mystifying; it is the science of human growth beyond its physical and intellectual dimensions.

The ‘I’ that appears in the baby is only an initial datum. It has to develop and expand in a big way. That is the great spiritual education of the child. The first education — and truly speaking, all education — is spiritual. The spiritual education of the child is to strengthen that ‘I’, that is, to strengthen its sense of individuality. Whenever the child wants to do something, the mother and others around encourage it, so that the child can understand its own worth as an individual and learn to stand on its own feet. Unfortunately, all over India today, this is the first as well as the last education of the child, and the result is an individual who is petty-minded, egotistic and unable to live and work with others. That is why we are in trouble. Sri Ramakrishna called this kaca ami, the unripe-I. This has only one capacity, namely, colliding with other ‘I’s. Bertrand Russell says that this human being is like a billiard ball, and billiard balls know only how to collide with each other. Sri Ramakrishna says that this unripe-I must develop into a ripe-I. That makes the individual grow into a person, making for happy relations with other people, for it is a very necessary spiritual education for peaceful and happy inter-human relations. If unripe-I stands for vyaktitva, individuality, ripe-I stands for vikasita vyaktitva, personality. Late Sir Julian Huxley, a British biologist, defines ‘personality’ thus: ‘Persons are individuals who transcend their mere organic individuality in conscious (social) participation.’

It is through seva-bhava, says Sri Ramakrishna, that this spiritual growth, the second stage in atma-jnana, takes place. Hence service becomes a training ground in the context of inter-human relations for the development of atma-jnana. ‘I am here to serve you, to help you, with whatever surplus energy of body and mind I possess’ — this attitude becomes natural when the unripe~I develops into the ripe-I. The proud and arrogant ‘I’ becomes the servant-I, the devotee-I — dasa ami, bhakta ami, as Sri Ramakrishna puts it. Sri Ramakrishna lays great stress on this subject. When the unripe-I expands into the ripe-I you expand spiritually, the Divine in you finds greater manifestation, and since the same Divine is in all beings, you become capable of entering into other people, and allowing others to enter into you, instead of colliding like billiard balls, as happens at the unripe-I level.

Consider a family where both wife and husband have unripe egos or strong individualities. There will be no peace in the house. If both have ripe egos, theirs will be a happy and fulfilled life. This applies everywhere. Today, in India, a little more of this ripe-I will make for better family and social life and better politics. Like this, there are beautiful teachings in the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, in the Holy Mother’s conversations, and in Vivekananda—literature, all of which are directly relevant to the health and well-being of our day-to-day life, individual and collective.

One great teaching of the Upanishads, the Gita, and Srimad Bhagavatam, which Sri Ramakrishna emphasized, is: ‘God is in every being and service of beings is the worship of God.’ He experienced the presence of the Divine in all, be they householders or young devotees, atheists or criminals. He would say: ‘I see Narayana in all of you.’ So he taught: Service of humanity is worship of God. Every jiva is Siva; service of the jiva is the worship of Siva. Vivekananda developed this into the universal philosophy and spirituality of service.

One of our weaknesses in India is that we hear a teaching but don’t know how to apply it intelligently. In this connection, Sri Ramakrishna’s parable of the Elephant Narayana and Mahut Narayana is helpful to us. A guru was living in an ashrama with his disciple. He had taught them that Narayana (God) is present in all beings. One day, the disciples went out to secure fuel and other things for the ashrama. Just then a mad elephant was passing on the road with the mahut on its back shouting: ‘Clear the way; a mad elephant is coming!’ Hearing this warning, all the disciples except one moved away to safety. That one disciple stood facing the elephant, chanting hymns to Narayana, disregarding the mahut’s constant warning to move away. The elephant, unfortunately, did not know this high Vedanta! It took hold of the youth, threw him aside and went on its way. Hearing about the incident, the guru and his other disciples came to where he was, brought him back to consciousness, and the guru asked him why, when all others moved away from the path of the mad elephant, he alone stood there. The disciple replied, ‘It is all your grace. You taught us that Narayana is in all beings; so I stood there worshipping the Elephant Narayana.’ The guru said, ‘What a fool you are! Narayana is certainly in the elephant, but is He not also in the mahut? Why did you not listen to the words of the Mahut Narayana?’ This is intelligent application of a teaching. Like this, there are many parables of significance in Sri Ramakrishna’s teachings.

Today is Guru Purnima. Sri Ramakrishna’s status as Guru of the whole humanity (jagadguru) has been proclaimed by many great thinkers and teachers. I shall now conclude this talk with a verse composed by Swami Abhedananda:

Jananim Saradam Devim

Ramakrsnam Jagadgurum;

Padapadme tayoh sritva

pranamami muhurmuhuh

‘Taking refuge at the lotus feet of Mother Sarada Devi and Jagadguru Sri Ramakrishna, I salute them again and again.’

[hr]

Talk given on the occasion of Guru Purnima at the Ramakrishna Math, Hyderabad, on 26 July 1991 by Swami Ranganathanandaji Maharaj, Vice-President of the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission.

Credits: Ramakrishna Math, Hyderabad & Vedanta Kesari (Mar-1992 issue)

[hr]