The activities of the movement associated with the name of Ramakrishna take two forms. There is the Mission, with branches all over the world, conducted by the members of the Order of Ramakrishna and devoted to works of charity and mercy which are at the service of all without distinction of race or creed; and there are also the Maths, places of prayer and meditation, where members of the Order retire from time to time for rest and spiritual refreshment. These two institutions, though obviously a close relation exists between them, are distinct organizations and independent of each other. The ideal of the ascetic, renouncing all in an endeavour to come nearer to God, has been known and reverenced in India for countless generations. The conception of a worldwide association of men all equally bound by vows of poverty, chastity and obedience but also actively engaged in rendering service to their fellow-men is, I think, of more modern growth. It is a conception not unfamiliar to us in the West, though there its historical development has followed different lines; but at the root of both the systems lies the idea of renunciation and service. It may be that in the West the obligation is assumed because of the belief in a divine injunction to feed the hungry, to tend the sick and to love one’s neighbour as oneself; whereas this Order of India believe that God is best served by serving man, because man is a manifestation of God. But in either case the obligation demands renunciation and service, and that kind of service which, rejecting every self-regarding motive, looks for no other reward than the knowledge that the service is given.

But both systems would be equally meaningless, if they did not postulate the essential spirituality of life. This was not an unknown doctrine in India, but I conceive the contribution of the founder of the Ramakrishna Mission to the development of religious ideas in this country to be this, that he saw the spiritual life not in terms of the individual alone but in those of a whole people, perhaps of a whole world. It is good that teachers should rise up from time to time who can preach with vehemence and conviction great truths like this; and I cannot doubt that these are the truths which our civilization must grasp and believe, if it is not to perish altogether.

The founder, believing that self-realization ought to be man’s supreme achievement, taught with all the fervour at his command that first of all man must secure the freedom of his own soul. In these days when the world is faced with an organised effort to bind the human race with fetters of iron, and things of the spirit are derided and denied, the last hope would indeed be gone if man abandoned the struggle for that freedom. No price can be too high to pay for it. It demands sacrifice and renunciation. And it is for this, and not for their ease or comfort, or any of their material possessions, that the democracies will have to fight, if fight one day they must, against the dangers that threaten them.

I think that the two qualities on the need of which the founder of this Mission insisted most of all were sincerity and simplicity. And by sincerity I suppose he meant that quality which rejects what is false, because it is never content with anything less than truth. It is perhaps the result at first of a conscious effort, but later on it becomes a habit of mind and a part of a man’s intellectual equipment, so that it is possible almost by instinct to distinguish the true from the false. In a world drenched with propaganda, when falsehood is deliberately made to masquerade as truth and people are fed with lies in the interests of a policy or an ideology, sincerity is not perhaps one of the virtues now in fashion; but I am old-fashioned enough to believe, though sometimes I find it difficult, that truth will in the end prevail. And so too with simplicity, which is another aspect of truth, since it implies the discarding of catchwords and shams, and of all the irrelevant things with which we have complicated and confused our lives.

Sincerity and simplicity are the qualities of a saint, but saints are not always practical men. And what I admire in Vivekananda also is his strong sense of reality and proportion. He reports his own Master as saying: “First form character, first learn spirituality, and the results will come of themselves.” This is the same conclusion as that of the great Greek philosopher that good acts are those acts which the good man does. Action issues from character; and it is not so much what a man does as what a man is. And I remember with pleasure one of the parables told by Ramakrishna himself. I mean the parable of the Guru, the disciple and the mad elephant. The story is that the disciple once encountered a mad elephant. Every one shouted to him to escape from its path and the mahout cried out, “Save yourself, save yourself;” but the disciple stood his ground and was attacked by the elephant and seriously injured. His Guru later on inquired from him why he had acted thus, to which the disciple replied that, having been taught that God was manifest in all life, he supposed that the elephant also was a manifestation of God and therefore no harm could come to him. But the Guru said, “It is true that God was manifest in the elephant, but was He not also manifest in the mahout, and even more so? Why then did you pay no attention to his warning?” So too on another occasion he is reported to have said, “A devotee ought not to be a fool.” And I think that Vivekananda’s sense of reality and proportion is shown most strongly in his foundation of the Ramakrishna Order, devoted not only to contemplation and meditation but also to the service of their fellow-men in order that they may the better serve God. I would never speak lightly of the exclusively contemplative life, in which many men and women have found happiness and peace; and there are countries to-day where people may well find in it the only escape from persecution and the miseries of a regimented existence. But in countries like India where the pulse of life beats strongly, and men are still allowed to think for themselves, the conception of a life of renunciation conjoined with service seems to me to have the higher value. But whether this be so or not, I do not think that the founder of this Mission hesitated between the two; and the extension of its work into so many spheres of human activity and into so many lands justifies the choice which he made.

The brethren of the Mission would be the first to admit that others have laboured, and are still labouring, in the same field. But they themselves do seem to me to represent the birth of a new idea destined to have far-reaching consequences. Here is a movement, issuing from Indian soil and based upon the adaptation or application of conceptions long familiar to Indian thought, but which has nevertheless given those conceptions a novel content and direction and has related them to modern needs. Its principles are those of unity and not division, of co-operation, not conflict; and the unity is a spiritual one, transcending divisions of caste and creed. Is there not here a great message of hope?

The picture of Vivekananda among his disciples, their equal and friend rather than their master, is a very attractive one. It was an English poet who wrote, “He prayeth best who loveth best, all things both great and small ;” and I may fitly conclude what I have to say by quoting words which Vivekananda is said to have used on two occasions. During an epidemic he said to one who complained of not being able to talk of religion when he came to see him, “So long as even a single dog in my country is without food, my whole religion will be to feed it.” And the other occasion was during a great famine when a devotee had maintained to him that the death of so many was a matter concerning only the victims’ Karma and was none of his business; to this Vivekananda replied in a passion of indignation, “Are they men, those who have no pity for men ?”

From our Archives: Published in Prabuddha Bharata, April 1939

[hr]

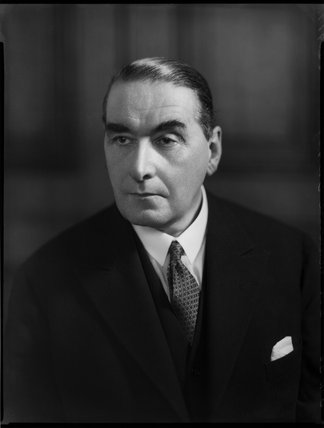

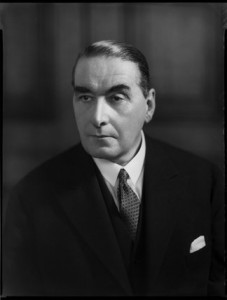

Sir Maurice Gwyer

Sir Maurice Linford Gwyer

(25 April 1878 – 12 October 1952) was Vice Chancellor of Delhi University (1938-1950), and Chief Justice of India (1937–43). Sir Maurice was educated at Highgate School. He is credited with having founded the prestigious college Miranda House in the year 1948 in Delhi, India.

In the Ideals of Swami Vivekananda, which is an illuminating address delivered at the Vivekananda Anniversary, Ramakrishna Mission, New Delhi, by the Hon’ble Sir Maurice Gwyer, K.C.B., K.C.S.I., Kt., Chief Justice of the Federal Court, India, he deals with the principles for which Swami Vivekananda stood, and emphasizes that the modern civilisation must grasp them if it is not to perish altogether.